Video Game Accessibility

Making Ava easier to play for autistic children

Role

UX Researcher at Open Mind School

Methods

Ethnography, Survey

Deliverables

Report, Presentation

Changes for Cognitive and Motor Accessibility

Result

A note on language

Historically there’s been a debate between person-first and identity-first language in describing autistic people. Similar to the Deaf community, autistic self-advocates endorse identity-first language, and I follow that convention here.

Context

Autism can and has meant many different things to many different people. It was first popularized as a medical term in the 1940s to describe a developmental condition in children involving impaired social interaction, communication, and restricted or repetitive behaviors. Other common features include sensory sensitivities and difficulty with fine motor skills. In the past few decades, however, this definition has increasingly been viewed as inadequate as people acknowledge that disability is not inherent to a person and instead arises from their interaction with the environment. Today there are many people (myself included) who view Autism not as a disability but as a source of neurodiversity to be valued.

This discrepancy in how Autism is viewed underlies a tension in treatments and therapies between “normalization” and “self-actualization.” Efforts to make an autistic person act neurotypical— that is, more “normal”—stem from well-meaning desires to reduce the friction between them and their social world. In practice, these therapies (namely Applied Behavior Analysis, or ABA) are deeply flawed, and autistic self-advocates describe them as traumatic and unhelpful. By contrast, self-actualization promotes the identity of the autistic person and is deeply intertwined with the personal autonomy to choose one’s own goals.

For this study I worked as the UX researcher for Open Mind School, a small inclusive K-12 school in Silicon Valley. My role was to provide research services to EdTech startups that wanted to be accessible but which would not otherwise have the expertise to recruit, accommodate, and conduct research with students who are autistic or disabled. One such company was Social Cipher, a small video game developer that had created Ava, a role-playing platformer designed to foster social and emotional skills (SEL) in middle school students. Ava was first designed with input from autistic self-advocates and SEL experts and then play-tested with students to gauge interest in the game. My objective as UX researcher was to evaluate the accessibility of Ava by identifying barriers to playing the game and providing recommendations to remediate them.

Collaboration with the Social Cipher development team

Method

Ava was offered as an optional 10-week elective course in Open Mind School’s Winter quarter. To enroll, students and their parents read and agreed to a consent form outlining the details of the study. In addition to collaborating with Social Cipher’s development team, I recruited our school’s counselor to teach the game’s associated SEL curriculum that accompanied each level. I also recruited our occupational therapist on a bimonthly basis to help describe and characterize the nature of students’ movements and motor impairments.

Eight students attending Open Mind School, ages 9-13, enrolled in the elective course. Several students were accompanied by 1-to-1 paraeducators who assisted with communication and emotional regulation. Classes were held in 30 minute blocks twice a week. At the beginning of each class, our school counselor taught the curriculum while I set up computer stations for the students. Each student was given a Chromebook laptop with the option to add an external keyboard and mouse depending on their preference.

Once the students started playing, I observed them, taking notes and intermittently providing tech support. Observations were made for difficulties accessing or playing Ava, adaptive strategies, game metrics and outcomes, body language, and quotations. When the occupational therapist was present, I also consulted with them on what I was seeing and the correct terminology to use. At the end of each week students were asked to complete a digital survey about their experience of the game and of the class generally.

An insight into my choice of method

Savvy readers might wonder why I chose a digital survey to record subjective experiences when I was already in-person and could have interviewed the students directly. The answer is that many autistic people experience difficulties communicating, and I knew several of my students were nonspeaking. Additionally, autistic people’s ability to communicate can be temporarily impaired by emotional dysregulation or the lack of an appropriate alternative and augmentative communication (AAC) device. For this reason, a digital survey was chosen to allow students the option to complete it later, at a time and place of their choosing.

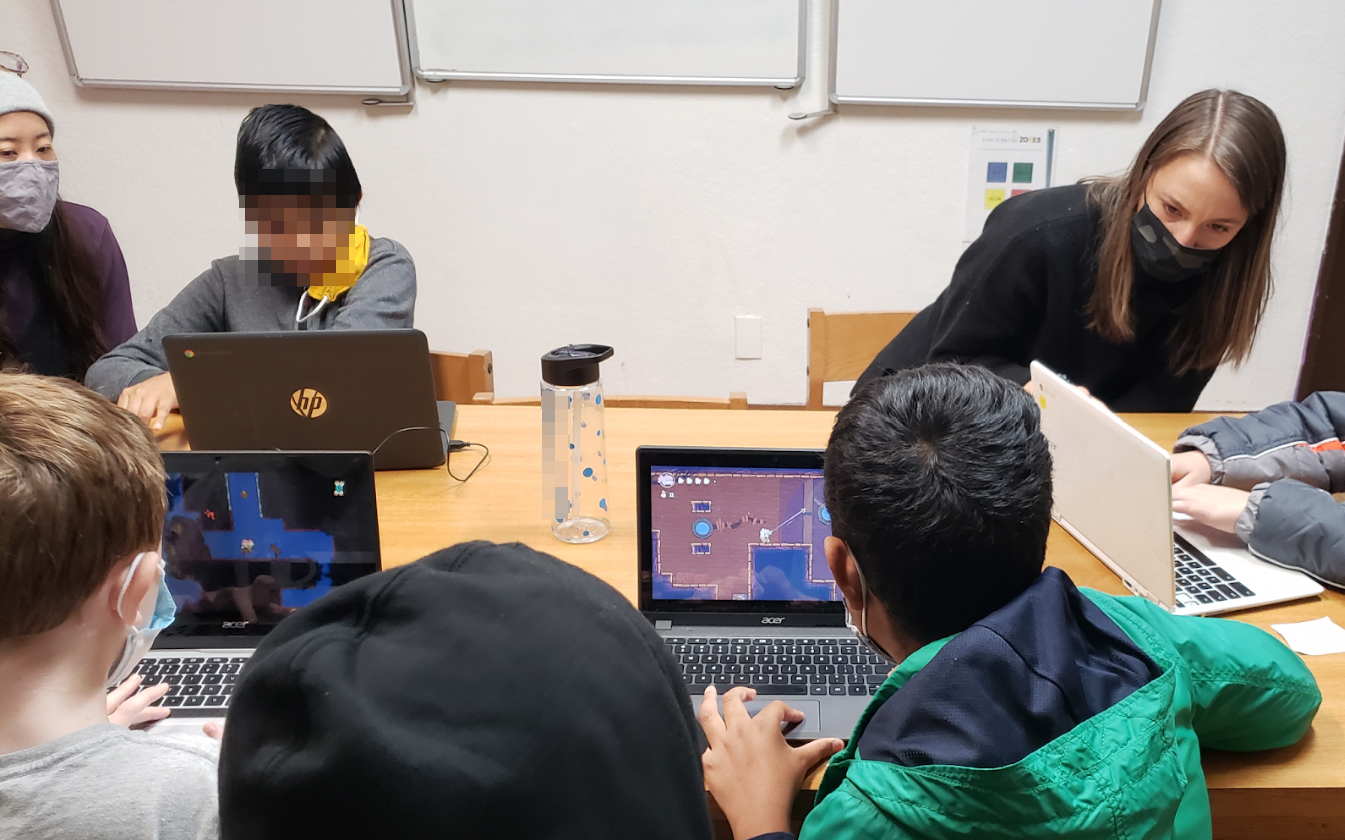

Students playing Social Cipher’s game Ava

Results

Insights from ethnographic observation and survey answers were synthesized to produce a written report and slide presentation for the Social Cipher development team. The most significant barrier to access was a particular set of assumptions about a player’s motor ability: assumptions that generally did not hold for Open Mind School’s autistic students. Students were observed to experience poor coordination, tremor, difficulty gripping, and difficulty with speed and timing, among other things. Some of these traits are classically associated with Autism and others were likely the result of a cooccurring condition. Additionally, although all the students had experience with laptops, a subset of students had never used a mouse before, which is critical to successfully controlling the “hook” feature in Ava. The ultimate result of this was that only one player was able to play fully independently, with the others requiring help in varying degrees.

To a lesser extent, students also experienced cognitive barriers to playing as well. Many students needed assistance remembering their passwords to access the game. Once in the game, some players forgot their current goal or were confused on where to go in the level to achieve it. One student had difficulty reading and needed written dialogue to be read aloud for them.

Fortunately, many of these barriers to access can be remediated. Recommendations to improve cognitive and motor accessibility were given. Options for keyboard remapping, changing input sensitivity, allowing other input devices, enabling text-to-speech, and adding a mini-map are just some of the ways that will facilitate autistic students playing more independently.